By Annie Zhanling Wang, Harvard University

“Ice foloho manju-i geren bithe” Qingshu quanji 清書全集 is an early Qing Manchu language primer that has not yet received extensive scholarly attention. It was printed in 1699 by Tingsonglou 聽松樓 of Nanjing, a publishing house that thrived in the Ming but slowly declined in the Qing. Since Manchu language books only started appearing in noticeable quantities in the 1670s, and the only earlier book of this genre that has received extensive scholarly treatment is Shen Qiliang’s Daqing quanshu 大清全書 of 1683, this book is a precious example of early Qing Manchu-language publishing.

Indeed, 1699 – over fifty years after the founding of the Qing – was a time when Manchu books were on the verge of entering a boom in terms of variety, complexity, and quantity. The Qing empire had left the initial stage of conquest and consolidation and entered what would be retrospectively deemed “the High Qing” period, and the Manchus and (at least a portion of) the Han were getting increasingly familiar with each other’s culture and language. At this historical juncture, what would a Manchu language book look like? This post focuses on the copy of Qingshu quanji currently kept at the Harvard-Yenching Library, previously belonging to Francis Cleaves. The post will discuss the material aspects of this copy, along with its format, para-text, content, and the people involved in its creation. Finally, the post will compare this copy with other existing copies of Qingshu quanji.

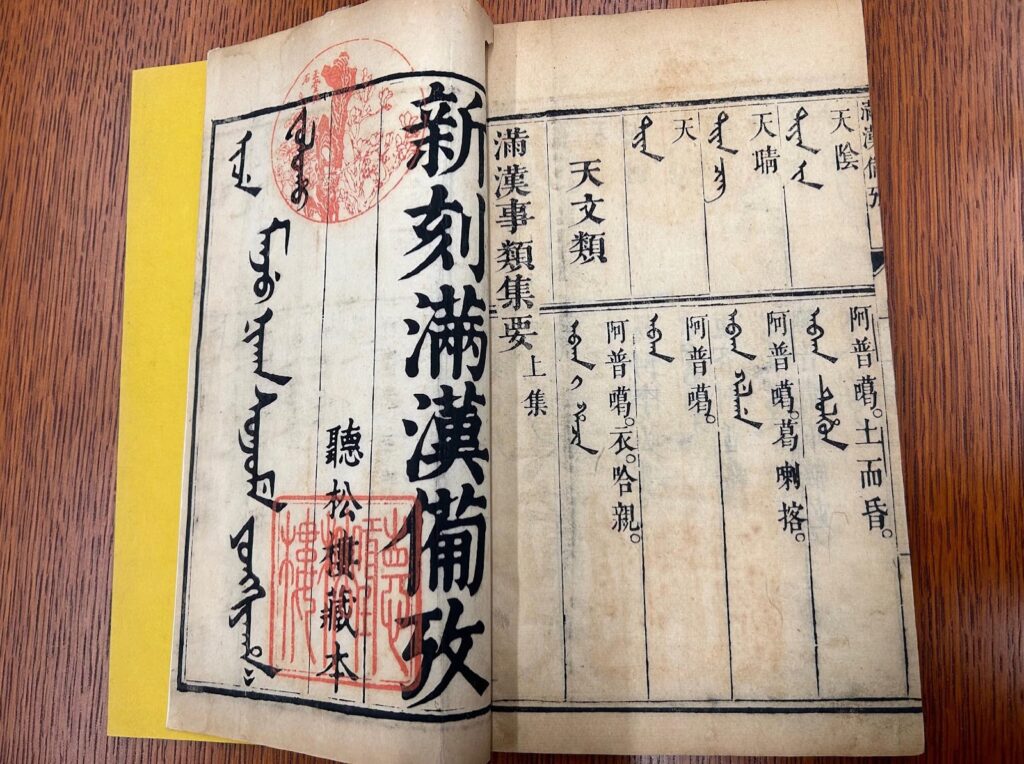

First, let us consider the materiality of the book. This set of Qingshu quanji 清書全集 leans on the small side (25.5cm*16cm) compared with most other Manchu books.1 The small size indicates that this book was less of an item of prestige, more of an item of utility. If we open the book, we will notice that there is a lot of blank space (for example, see figures 2-5), which shows that the publisher put a lot of money into this book but still expected there to be a group of willing and relatively well-off buyers. We will also notice that the pages are very brittle – reasonably so after three hundred years – compared with some language books commissioned by the palace.2 This, again, shows that the book was meant to be not luxurious but economical. Finally, we will also see that the Manchu print, though clear enough to be read, is a little crude compared with that in later books, which suggests that the printing of Manchu letters might not have been maturely developed and streamlined in Nanjing as of 1699.

Next, let us consider the format of the book. The book has five fascicles, four of which open from the left to the right, in the style of most Manchu books. But the first fascicle opens both ways. If you open it from the left, you will start reading the twelve syllabaries, all in Manchu. If you open it from the right, as with a Chinese book, you will encounter two prefaces, some explanatory notes (fanli 凡例), and a table of contents, all written in Chinese. On both the left end and the right end of the fascicle there is a bilingual title page. That the fascicle opens both ways shows that the publisher, while abiding by conventions of Manchu books, still considered the reading habits of a Chinese reader.

Now, let us consider the paratext and the people involved. The book has two prefaces. The first is by Wang Hesun 汪鶴孫, who referred to himself as the tongxuedi 同學弟 of the compiler of the book, Chen Kechen 陳可臣. On this basis, we can conclude that Wang and Chen studied together or at least under the same teacher, and that Wang was the more junior of the two. In his preface, Wang writes about the close association between the Manchu script and the founders of the Manchu dynasty; mentions the institutional setup where all Hanlin Academicians were to learn Manchu; brings up the perks of becoming a Hanlin Academician, where one can enjoy access to the precious books in the Academy while doing translation work; describes his friend and the compiler, Chen Kechen, as a gifted and erudite scholar who holds a strong interest in the Manchu language, who is good at revising Manchu language books and putting them together. According to Wang, because those who wanted to study Manchu found Chen’s materials so easy to use, they asked Chen to publish them so that beginners of Manchu could benefit. Chen, hearing the request, put together the materials he used on his journey towards the civil service exams, which became this compilation. Wang ends the preface by noting that as Chen taught the Manchu script at the History Office 史館, the ministers all admired Chen’s learning, “No wonder that we find learning laborious and difficult, while Chen finds it enjoyable and easy!” This preface, dated 1699, centers on the social realm of Han literati who studied together, who pursued similar official careers shaped by Qing institutions. Such Han literati sociality – marked by the sharing of materials, the admiration for erudite peers, the experience of studying together, and the common pursuit of the scholar-official life – is central to understanding Qingshu quanji. At the end of the day, both the compiler and the readers of this language book came from this same group of people, for the common goal of obtaining official careers through Qing institutions.

The second preface, written by Ling Shaowen 凌紹雯 also in 1699, reiterates some of the same themes. But there is something surprising about this piece: it is only through this second preface that we learn that Ling is also a compiler of this collection. After associating the Manchu script with the founding of the dynasty and the early Qing emperors, Ling says that he and his friend Chen Kechen have been studying Manchu together for years; in this process, they got some Manchu-Chinese language book(s) from the capital city; they found these materials so illuminating that they made a compilation so that these could be shared with more men of letters; he feels that he is too humble to write a preface, but since these materials are so valuable, he will puts them into print to share with his fellow scholars. Indeed, here we again see the centrality of the social circles of Han literati to the printing of Manchu language books. But isn’t it strange that the first preface does not mention Ling at all? The first preface lavishes praises for Chen’s talent, and it speaks as if Chen alone compiled the work. Only the second preface – written by Ling himself – acknowledges his own role as a co-compiler. What should we make of this?

But let us now turn to the content of the collection. This set of Qingshu quanji has five fascicles (some other editions have different numbers of fascicles, see below). The first one is titled “Twelve Syllabaries of the Qing Script 清書十二字頭” and indeed consists of the twelve syllabaries, in addition to the prefaces discussed above and the table of contents. This makes sense as the first volume for a beginner, since throughout the Qing, the Twelve Syllabaries indeed enjoyed the solid status of the first thing that a student of Manchu was supposed to learn (Saarela, 52). The second fascicle, titled “Coordinating the Qing Script to the Sound 清書對音協字,” gives multiple Chinese characters whose pronunciation accords to a certain Manchu syllable. For example, after the Manchu script “ke,” it gives four Chinese characters 客刻尅克 (all pronounced as “ke”) and after the Manchu script “gi,” it gives as many as 32 Chinese characters including 吉計骥既及給暨 (all pronounced as “ji” in pinyin, which is close to the Manchu sound “gi,” pronounced with a hard g) (figure 2). This fascicle could be a tool for Chinese speakers to learn the pronunciation of Manchu syllables. By providing multiple Chinese characters, the compiler is likely hoping that readers would at least recognize some of them.

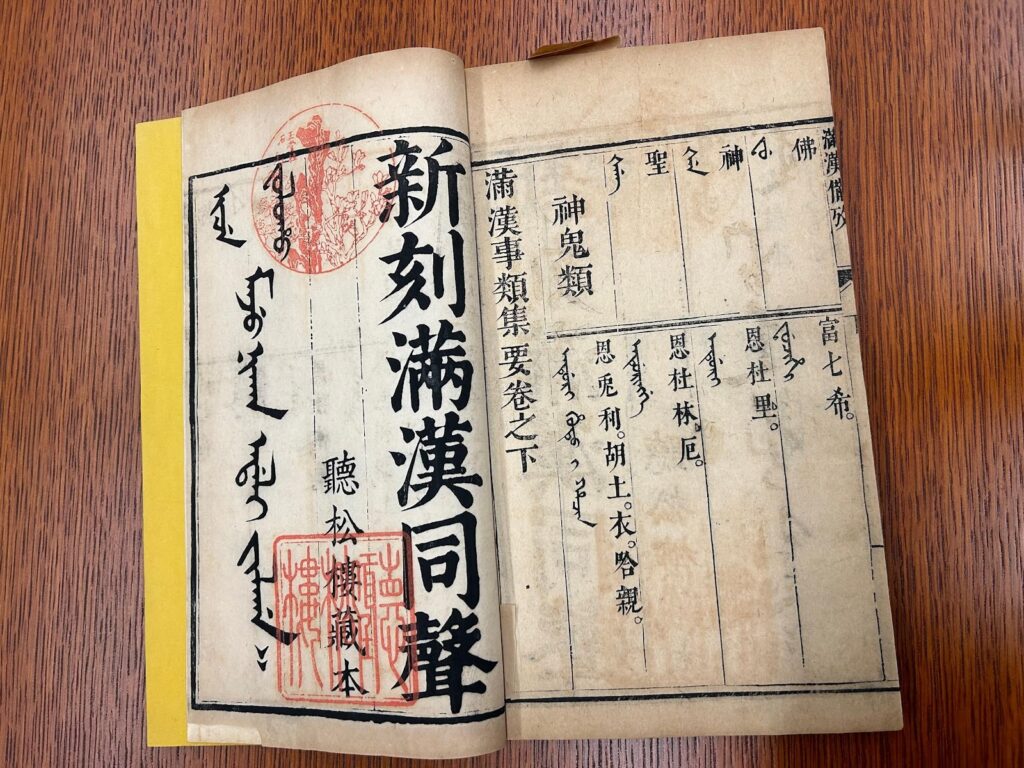

The third fascicle, “Newly Printed Preparation for Manchu and Chinese” 新刻滿漢備攻, and the fourth, “Newly Printed Manchu and Chinese of the Same Pronunciation” 新刻滿漢同聲 – despite their different titles on the cover pages – are in fact from the same collection “Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese 滿漢事類集要.” Fascicle 3 is the first half 上集 of “Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese,” Fascicle 4 the second half 下集 (figure 3). The blockheads (banxin 版心) – the tiny blocks at the middle of the vertical margin of each page – in both volumes say “Newly Printed Preparation for Manchu and Chinese,” (figure 3) which is the title of Fascicle 3 on the cover page. Why are the titles on the cover pages of both fascicles different, when in fact they are two parts of the same collection (whose name is different from the names on both fascicles)? There could be multiple explanations. Perhaps the publisher thought that if the two fascicles have different names, readers would think of Qingshu quanji as a whole as more colorful and comprehensive. Perhaps the same work, in different prints, carried different names. We cannot know for sure, but this multiplicity of titles does show that the same content could be recycled again and again, under different titles in different printed versions.

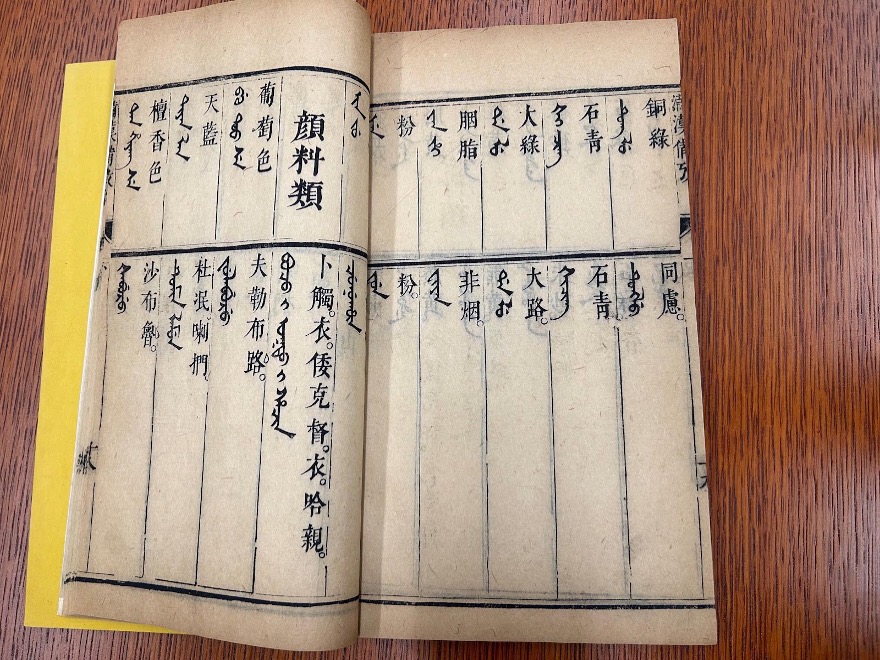

As for the content of these two fascicles, they list vocabulary under various categories such as “Music” 音樂類 “Gods and Ghosts” 神鬼類 “Horses” 馬匹類 “Beasts/Animals with Feet” 走獸類 and “Fruits and Vegetables” 蔬果類. There are 32 categories in total. Each page is divided into an upper column and a lower column (figure 4). In the upper column are Chinese words with their pronunciations in Manchu transcription. In the lower column are the Manchu words – of the same meaning as the Chinese words in the corresponding upper column – with their pronunciations in Chinese transcription. These two fascicles can be used by Chinese readers who want to learn Manchu as well as Manchu readers who want to learn Chinese.

The last fascicle – “Essential Sayings in Manchu and Chinese 滿漢切要雜言” – consists of words and phrases deemed important in day-to-day life. Like the previous two fascicles, this one consists of two columns, the upper column of Chinese words with their pronunciations transcribed in Manchu, the lower column the opposite (figure 5). It is interesting to think about what is considered “essential” 切要 here. The very first words in the fascicle mean “rich” “exalted” and “poor” (figure 5). There are also phrases about going to places for socialization such as “why don’t you come here?” “I will naturally come [to your place] soon,” “They won’t go,” “What’s the point of going?”; and words and phrases about (social) eating and drinking such as “make meals” “eat” “drink alcohol” “eat meat” “I’m full” “eat more” and “thank you.” Much of the content, as we can see, is about social life.

Do such phrases really pertain to civil service exams, translation exams, and official careers, as the prefaces indicate? We cannot be sure. But from Qingshu quanji, we do see that there is both an official culture of the exalted and professionally useful Manchu language (as exemplified in the preface), on the one hand, and a lay culture of day-to-day Manchu language in real-life scenes (as exemplified in the last fascicle on daily phrases), on the other. Qingshu quanji can be used by both Chinese speakers who study Manchu and Manchu speakers who study Chinese. A Chinese speaker can use volumes one to five, following a trajectory from the pronunciations of the Manchu syllabaries to some important vocab to the essential phrases in everyday life. A Manchu speaker can use volumes two to five, learning the pronunciation of Chinese characters and common vocab and real-life phrases. Qingshu quanji can indeed be used by different readers who are either beginning to learn Manchu or learning some useful Chinese with some foundation already.3

Finally, let us consider the issue of editions and copies. According to Kanda Nobuo, Qingshu quanji is rare, with a small number of existing copies. Beside the Cleaves copy at the Harvard-Yenching Library, there is a copy at Keio University in Tokyo, also in five volumes but lacking title pages, printed partially from different blocks. Kanda notes that this Keio copy seems to have been printed a little later than the Cleaves one (Kanda, 68). If that is the case, then we can see that there was indeed a market for this book, that there were enough buyers for the publisher to issue a reprint.

Tatiana Pang has also described a copy in Russia. Interestingly, this edition has only four fascicles instead of five. While the first fascicle is the same as that in the Cleaves copy, the second and the third fascicles in the Pang copy seem to equate the third and fourth in the Cleaves copy, both titled “Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese” 滿漢事類集要 (Pang, 115-6). Pang adds that the fourth fascicle is “an addition to the dictionary,” and it is not clear what that means. Moreover, there is a copy whose digital version has been published by Leiden University. Interestingly, this copy has only three fascicles, but it seems to cover all the content covered by the Cleaves edition, only that the fascicles are divided up differently. The first fascicle contains both “Twelve Syllabaries of the Qing Script 清書十二字頭” and the “Coordinating the Qing Script to the Sound 清書對音協字,” which are the content of the first two fascicles in the Cleaves version. The second fascicle covers the first part of 滿漢事類集要 “Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese” (at the very end of that fascicle, it says 滿漢事類集要 上卷終“Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese, first volume, end”), which in the Cleaves edition is the third fascicle. The final fascicle in the Leiden version contains the second half of the 滿漢事類集要 “Categories of Words in Manchu and Chinese” as well as the “Essential Sayings in Manchu and Chinese 滿漢切要雜言,” which are the contents of the fourth and fifth fascicles of the Cleaves edition.

Together from these editions, we can see that the division of fascicles could be flexible and did not affect the totality of the content. We can also see that even when the content is “incomplete” – when the content of the five volumes in the Cleaves edition do not all get covered in a particular edition – the edition still got printed, and we can surmise that there were buyers. Different combinations of language books could be sold and bought under the same title, and buyers likely considered all these various combinations helpful for language learning.

Overall, Qingshu quanji shows how Manchu language books were a part of the Han literati social life; how a Han learner might have learned Manchu; how an early Qing publisher designed a set of language books for a selected but reasonably wide audience with the hope of good sales; and how different editions reveal the flexibility, practicality, and popularity of such language books.

The author wants to thank Sarah Bramao-Ramos for answering numerous questions in the research process

- For example, “Han-i araha manju gisun-i buleku bithe” Yuzhi Qingwen jian 御製清文鑒 (1708 copy at the Harvard-Yenching Library, call number Ma5806.05/2490) is 30.2cm*19.3cm, while “Daicing gurun-i yooni bithe” Da Qing quanshu 大清全書 (1713 copy at the Harvard-Yenching Library, call number Ma5806.05/4385) is 30cm*17.7cm.

↩︎ - Such as Yuzhi Qingwen jian cited in the previous footnote. ↩︎

- A similar point is made in Sarah Bramao-Ramos’ dissertation, “Manchu-language Books in Qing China,” Harvard University, 2023. ↩︎

References

Bramao-Ramos, Sarah. “Manchu-language Books in Qing China.” PhD thesis, Harvard University, 2023.

Kanda Nobuo. “Present State of Preservation of Manchu Literature.” Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 26 (1968), 63-95.

Pang, Tatiana. Descriptive Catalogue of Manchu Manuscripts and Blockprints in the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences. Wiesbaden, 2001.

Saarela, Mårten Söderblom. The Early Modern Travels of Manchu: A Script and Its Study in East Asia and Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.