Sarah Bramao-Ramos is a Research Assistant Professor at the Society of Fellows in the Humanities at the University of Hong Kong.

If you go to any library and ask to see a Manchu-language book created in the Qing (1644–1911), you’ll likely be brought a stack of stitch-bound fascicles (Ch. xianzhuang 線裝, also translated as “thread binding,” “side-sewn,” “stabbed,” or “side-stitched”). Each fascicle will likely have an inner and outer ‘stitch.’ First, there will be an inner twist of paper (also called a “paper nail,” Ch. zhi ding 紙釘), which holds the text block together. Then there will be a thread, which secures the cover to the text block. Depending on the length of the book the fascicles might then be contained within a case (Ch. shutao 書套), wrapper (Ch. hanhe 函盒 or hushu 護書), or boards (Ch. jiaban 夾板). Thus secured, the fascicles will be protected from dust and the elements and stored horizontally.

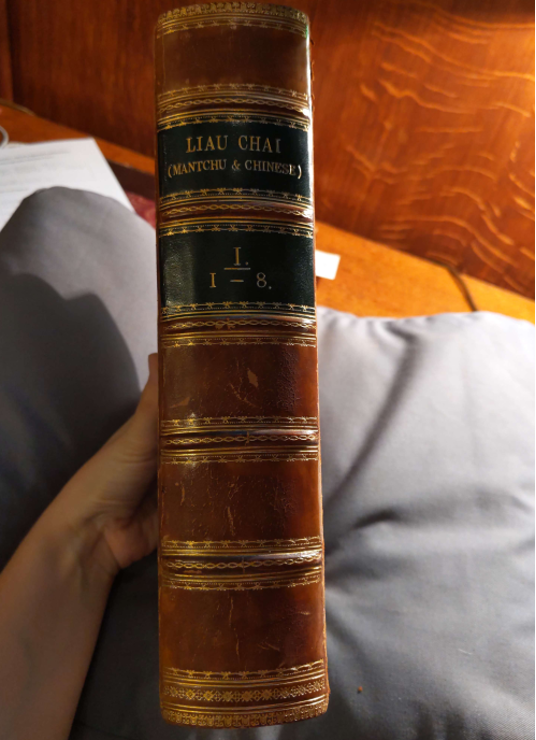

In some collections, however, you might be brought a book that looks quite different:

Figure 1: A copy of the Manchu translation of Liaozhai zhiyi 聊齋誌異/Sonjofi ubaliyambuha liyoo jai jy i bithe (Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio), Crawford 367, John Rylands Library. Volume one of three. Photograph by the author.

The example above is a Manchu-Chinese book, rebound in Western-style binding. Through rebinding, the original character of the book has been entirely altered. Though the contents were once divided and bound as twenty-four fascicles (Ma. debtelin, Ch. juan 卷), it is now in three volumes. It also has no thread and no original cover. In other words, it presents itself as a Western book, designed to be stored vertically on a shelf. In some collections this rebinding was quite carefully and sympathetically done, meaning that the rebound fascicles can still be opened and read. In others, however, numerous fascicles have been combined and rebound very tightly together, meaning that opening and turning the pages is now quite tricky.

The practice of rebinding in Europe, where this book now is, is not at all limited to Manchu-language books, of course. Though we might frown upon it today, especially in light of current conservation trends towards adopting non-invasive preservation methods, rebinding used to be a routine part of a European book’s lifespan. Up until the nineteenth century, at least some books in Europe were sold unbound or stitched in fragile wrappers, and their owner would have to take them to be bound or rebound. Even if preservation wasn’t the primary concern, owners might rebind their books to enhance their worth, create the illusion of a more valuable book, or simply to suit their own tastes. Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), for example, an avid seventeenth-century London book collector, had the backs of hundreds of his books gilded, “to make them handsome.” He was immensely pleased with the results, spending entire evenings at his bookbinders to watch him work. Rebound books were also often intended to be gifts, perhaps an author’s presentation copy gifted to an important patron, or a Bible intended for a soon-to-be bride.[1]

It is difficult to say with any authority what percentage of extant Manchu-language books have been rebound in Western bindings. Catalogues — indispensable research tools though they undoubtedly are — don’t typically record information about bindings, so it is only by methodically looking at physical books that you will come across them. That said, I have found such books in collections across both Europe and America, and it is particularly ubiquitous in some, including the Cambridge University Library, the John Rylands Library, and (so Elvin Meng assures me) the books in the Erich Hauer collection at Johns Hopkins University.

As with bindings more generally, rebinding indicates some of the history of these books, suggesting who might have used them and why. Unlike other kinds of rebinding, however, the rebinding of East Asian books with Western bindings reflects the mixed reception these books likely received. It hints at how unfamiliar book owners and libraries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were with East Asian books and bindings. The decision to remove what were likely perfectly good thread and paper bindings and replace them with boards, leather, and glue conveys the once-standard perception that Chinese bindings were inadequate and Chinese book formats were inconvenient, what with their multiple fascicles and cumbersome shelving requirements (horizontal rather than vertical).

At the same time, such rebindings are also a strong indication that East Asian books were once valued. Even if owners and libraries didn’t know what to make of the books, they still wanted to show them off. Figure 1, for instance, once formed part of the Bibliotheca Lindesiana, an extensive library amassed by the Earls of Crawford — Alexander Lindsay (1812–1880) and Ludovic Lindsay (1847–1913) — that contained over three thousand oriental books and manuscripts. Though Alexander Lindsay only knew Persian, he still collected books in Turkish, Samarian, Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Greek, and Arabic, among other languages, and was continually looking for “the best and most valuable books, landmarks of thought and progress, in all cultivated languages, Oriental as well as European.”[2] Having obtained such books, he had them rebound, possibly by the London bookseller Bernard Quaritch (1819–1899). Almost all of the Chinese and Manchu books in Bibliotheca Lindesiana, now in the John Rylands Library, are in typical nineteenth-century European style binding, with marbled boards and half leather binding (spine and corners). With the title and other information tooled on the spine, these books were ready to be placed vertically alongside the other books in this grand private collection.

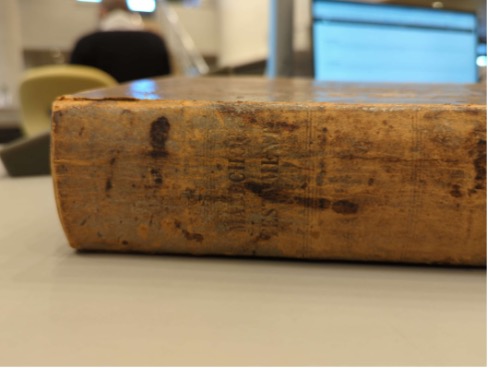

Through rebinding, owners were able to make their East Asian books accord with what they thought a book should look like — something that was particularly important when it came to devotional books. Though I have not come across a Manchu-language book with bindings made of metal and precious stones, rebinding Bibles in Manchu seems to have been common. A copy of Muse-i ejen Isus Heristos-i tutabuha ice hese (literally “The new proclamation that our lord Isus Heristos left,” known more commonly as the New Testament) in The Royal Danish Library (Det Kgl. Bibliotek) in Copenhagen, for example, has been rebound, and it now has a stately leather cover and a spine that reads “Mandchou Testament.” As the bookbinder’s ticket inside the front cover indicates, it was Burn and Company, one of the bookbinders employed by the British and Foreign Bible Society, that gave the book bindings considered more suitable for its esteemed contents.

Figure 2: Muse-i ejen Isus Heristos-i tutabuha ice hese/Wu zhu Yesu Jidu xinyue shengshu 吾主耶穌基督新約聖書 (The new proclamation that our Lord Isus Heristos left), Manju 81, Det Kgl. Bibliotek. Photograph by the author.

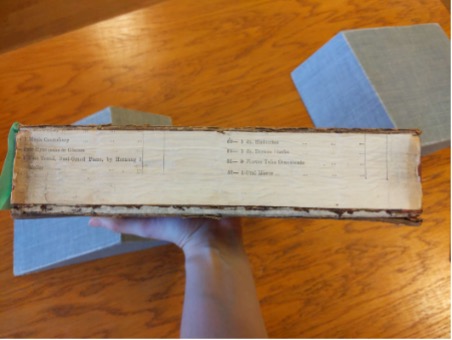

Occasionally, if the rebinding is in poor shape, it provides a literal glimpse into the practice of repurposing paper to make bindings and boards. Such is the case with the trilingual Ilan hacin-i gisun kamcibuha tuwara de ja obuha bithe/Sanhe bian lan 三合便覽/Γurban jüil-ün üge qadamal üjeküi-dür kilbar bolγαγsan bičig (A Trilingual Glossary for Easy Browsing), now at the Jagiellonian University Library in Kraków. Like many of the books in the collection, this one has been rebound with marbled boards, but because the new binding is damaged, it is possible to see that recycled paper — what seems to be an inventory list of some sort — was used to line and build the new spine of the book.

Figure 3: Ilan hacin-i gisun kamcibuha tuwara de ja obuha bithe/Sanhe bian lan 三合便覽/Γurban jüil-ün üge qadamal üjeküi-dür kilbar bolγαγsan bičig (A Trilingual Glossary for Easy Browsing), Moellendorff 1, Jagiellonian University Library. Photograph by the author.

While some rebinding projects involved only a handful of books, others were more comprehensive. The Manchu books at the Cambridge University Library, for example, were rebound en masse in the 1950s and 1960s, along with all the Chinese and Japanese books. This work was done by workers employed by Remploy (1944–present), which provided “sheltered employment” for those who wanted to work but were considered too severely disabled to gain and keep employment, including disabled veterans. Along with woodworking, broom making, leatherwork, and printing, rebinding East Asian books in Western binding seems to have fit the need to create employment opportunities.

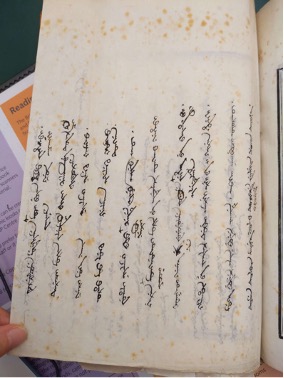

Rebinding can also result in the somewhat unexpected preservation of ephemera. Such is the case with a copy of Han-i araha alin-i tokso de halhūn be jailaha ši/Yuzhi Bishu shanzhuang shi 御製避暑山莊詩 (Imperial Poems on the Mountain Estate for Escaping the Heat) now at the British Library. As introduced by Richard Strassberg and Stephan Whiteman, this poetry collection contains thirty-six poems and accompanying illustrations and was printed in two monolingual fascicles, one entirely in Chinese, and one in Manchu. The poems were first written in Chinese but translated into Manchu beginning in 1713. The copy in the British Library of the Manchu-language fascicle was rebound in Western binding, likely when the book first entered the collection in 1874. In the process, what was once a loose sheet of paper came to be bound as part of the book itself, though it was bound upside down:

Figure 4: Han-i araha alin-i tokso de halhūn be jailaha ši/Yuzhi Bishu shanzhuang shi 御製避暑山莊詩 (Imperial Poems on the Mountain Estate for Escaping the Heat), 19957.c.4., British Library. Photograph by the author.

As this sheet of paper is now upside down and in the middle of a poem, it seems that its inclusion was a complete mistake, something of a fluke. The writing itself, however, is not random. It reads as follows:

tumen tulbin majige šolo

tucikedebisirede fulgiyan duka tucike.When I had a bit of leisure

to go outamid the myriad matters, I went out of the red gates.muke buyere alin buyere jakade. absi nakabuci ojorakū.

As I longed for the sea and longed for the mountains, how could it be stopped?

halhūn be jailara dubei amargi ergi ba-i siren huweki.

To escape from the heat, [I] come to the far north where the land is fertile.

toksoi sengge

bede fujurulamefonjime[+iletulehe] wehe be baihabibi.Inquiring

ofto the old villagersasking[about where I could] foundind the [+public] stonewas,geren [+yooni] monggosoi morin be adulara ongko sehebi

They said that this was the grazing land where [+all] the Mongols pastured their horses

fuhali niyalmai boo [+seri]

akūdade eifu/inu[3] akū.Human dwellings were always completely [+sparse]

noneand there are no graves either.orho moo luku galman iseleku [+

komso]tongga.Grass and trees are dense, mosquitos and scorpions are

few[+rare].šeri muke sain niyalmai nimeku komso.

The spring and water are good, and there are few people who are sick.

tereci morin yalu

mefi biraidalaka[+biturame] tuwaraci de.After this, when I rode my horse [+along the edge]

the headof the river to have a look,

forgošomemudakiyame [+wainame]mooibujan šuwafihebi[+canggi]There was [+nothing but]

filled withthespinningwinding [+crooked]tree’sdense forestsniyalmai hūsun-i

untuhuri[+teodeme]ilibure[+arara] be baiburakūhakūThe

simple[+transfer] of human power had not been needed toerect[+create] [anything]

agu[+suwe]sikingkan [+king cui]-i forin-i gese hada be sabuhakūn.

SirDon’t [+you all] see the rocky summit, like a blow from the musical stone [+king cui],[4]

teile cokcohon-i alin weri[+cob seme meitehe [sic] ninggu-i] dergi ergi deiliha bi[+colgorokobi].

Only the vertical mountain[+abruptly] rising upstoodfrom theother[+top of the] eastern slopegeli [+saburakūn] tumen holo-i jakdan

saburakū bime[+moo fik sere bujan] be.Do you also [+not see], the [+forests] in the myriad valleys are [+thick with] pine [+trees]

not see,elbe

me[+hengge]dasihasalgabun wen-i adali ududu bujanhašabumebanjihanggenuhu.all the forests

encompassingin the high places, hanging downcovered formed, as if [formed] by Nature.

[Illegible]sukdun[+hūwaliyambume hūwašabure elden] enggelefime [+wasika] silenggifoson be alimbigilmarjambi.

[Illegible]The [+fallen] dewaccepting the sunlightglitters, receiving the [+harmonizing nurturing light]spirit.niowari niowari-i boco forgošome aniyadari ambula bargiyaha [+elgiyen oho]..

[Everything] turns green in turn every year the great harvests [+are bountiful].

As the numerous insertions and deletions indicate, the text is incomplete, and it appears to be a now-abandoned work in progress. In many places the writing is faint, as if written with a brush that didn’t have quite enough ink on it, and generally messy. While it is entirely possible that more than one writer was involved — one writer writing the original lines and a second making the corrections, perhaps — the writing is similar enough that it is hard to say for sure. Given the similarities in handwriting and the fact that both the original text and the corrections were written in black ink, I don’t believe these corrections were written by a teacher. As can be seen in teacher-corrected manuscripts like Muwa gisun, teachers certainly didn’t hesitate to make their corrections known, but they tended to favor red.

In most cases, the corrections have to do with deliberations over word choice. The writer (if indeed it was just one) seems to have been debating between a few different words, and then changing their mind. If there were two (or more) writers involved, we might imagine that one wrote the initial translation, which the second then made some additions to. When it came to explaining how few mosquitos and scorpions there were, for example, the text started with komso (“few”) but then was changed to tongga (“rare”). In the line about the pine trees, “do you not see?” (Ma. saburakūn) was originally written at the end of the phrase, but it was then decided to move the word to the beginning. Given how incomplete the manuscript translation is, I believe it is a draft, something that the anonymous writer (or writers) was working their way through.

But if you have read Bishu shanzhuang before, you might notice that some of the lines in the draft sound familiar. That is because the piece of paper appears to be a draft translation of the second poem in the collection, Ling jy i jugūn tugi i dalan/Zhijing yundi 芝逕雲隄 (“A Lingzhi Path on an Embankment to the Clouds”). The printed Manchu translation of the poem continues for quite a few more lines, but the relevant section is as follows:

tumen baita-i majige šolo de fulgiyan duka be tucimbi.. muke be buyere. alin be buyere be ilibume muterakū.. mo-i amargi bade halhūn be jailame jici muke boihon huweki. gašan-i sakdasa de fujurulame fonjime. bei wehe be baiha. geren i gisun. monggo-i morin adulara ongko. niyalmai boo seri bime. olgoho giran akū.. orho moo luku. galman hiyese akū. šeri muke sain. niyalma de nimeku komso sembi.. tereci morilafi birai biturame tuwaci. mudalime wainame bujan šuwa fihekebi.. šehun bigan be miyalime den fangkala be kemneme tuwaha. tokso usin be acinggiyahabuhakū.. moo be ume argire [sic][5] sehe.. ini cisui abkai banjibuha na-i šanggabuha arbun-i ba. niyalmai hūsun-i teodeme arara be baibuhakū.. suwe saburakūn. ging cui fung hada. cob seme meifehe ninggu-i dergide colgorokobi.. geli saburakūn. tumen holo-i jakdan fik sere bujan be lasariname elbihengge salgabun wen-i adali.. hūwaliyambume hūwašabure elden. enggeleme. wasika silenggi gilmarjambi.. niowari niori boco forgošome nurhūme aniya elgiyen oho..

When I have a bit of leisure amid the myriad tasks I leave the red gates. Longing for the sea and longing for the mountains, I am unable to stop. When I came to the northern mo to escape the heat, the water and earth were fertile. Asking the old men of the village [about where I could] find the stone stele, they all said that there was grazing land for the Mongols to pasture their horses. Human dwellings were sparse, and there were no skeletons either. Plants and trees are dense, and there are no mosquitos or scorpions. The spring and water are good, they said, and few people fall ill. After this, when I rode along the riverbank to have a look, I wandered along crooked paths, [seeing] everywhere filled with dense forests, gauging the vast wilderness, measuring the highs and lows. [I] did not touch the villages or fields or prune the trees. The form of the land was naturally begotten by Heaven, not the result of the transfer of human power. Don’t you all see that cui fung summit suddenly rises up from the top of the eastern slope? And don’t you also know that the forests of the myriad valleys are thick with pines, hanging down invitingly, as if [formed] by Nature? The fallen dew glitters, receiving the harmonizing, nourishing light. The bright shining green colors revolve in a series, the year was bountiful.

These two translations are most definitely related, but not at all the same. This is clear even from the very first line, when both translations describe going out of the “red gates” (Ma. fulgiyan duka) — undoubtedly a translation of dan que 丹闕 (“red palace”) in the Chinese — but while the printed translation has the speaker busy with myriad “tasks” (Ma. baita), the other is bogged down with “matters” (Ma. tulbin). Though both want to escape the heat (Ma. halhūn be jailara), in the printed text the speaker heads to the “northern mo,” a transcription of the Chinese word for desert (mo 漠). Curiously, neither uses gobi, the more common word for desert. In the other they head to the “far northern side” (Ma. dubei amargi ergi), yet in both the land is described as being “fertile” (Ma. huweki). The differences continue: in the printed text they ask the “old men of the village” (Ma. gašan-i sakdasa), while in the draft it is the “elders of the village” (Ma. toksoi sengge); in the printed text there are no “skeletons” (Ma. olgoho giran, literally “dry corpses”), yet in the draft there are no “graves” (Ma. eifu). In some places the two texts arrive at virtually the same meaning, though they use different words to get there, for example in the printed text he “rides” (Ma. morilafi) along the river, but in the draft he “rides his horse” (Ma. morin yalufi). The differences in the later lines are even more striking. The draft entirely skips the details about the vast wilderness, measuring heights, and refraining from pruning (Ma. šehun bigan be miyalime den fangkala be kemneme tuwaha. tokso usin be acinggiyahabuhakū.. moo be ume argire [sic] sehe..). It also omits the detail about Heaven (Ma. abkai) being responsible for the magnificent scenery.

What is going on here? It appears that someone tried their hand at translating this poem into Manchu, only to increasingly doubt which word they should use, skip a few lines, and then abandon the endeavor altogether. If more than one writer was involved, then both seem to have given up the project. Perhaps they thought they could produce a better Manchu translation of the original, for the printed text, even though it is associated with the famous translator Hesu (Ch. Hesu 和素) (1652–1718), is stilted and wooden. It has none of the formal features associated with Manchu-language autochthonous poetry, employing no end-rhyme. It utterly lacks the flair displayed by Jakdan (Ch. Zha-ke-dan 扎克丹) (ca. 1780s–after 1848) in both his translated and original poetry, or even the haunting lyricism of the anonymous nineteenth-century poetry collection Staatsbibliothek 34981. Maybe after wading exasperatedly through some of the printed book the anonymous reader decided to pull out a spare sheet of paper and see if they could improve on the original. If so, that might be why each line of the poem appears as a separate line, for if they could not make the words lyrical, they could at least create the appearance, through layout alone, that the lines were supposed to be poetic — the same approach taken in the similarly unpoetic translations in the Gin ping mei bithe/Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅 (The Plum in the Golden Vase).

For all that rebinding is destructive and erases valuable historical evidence, therefore, in the case of this book it has preserved this rare glimpse of at least one reader/writer of Manchu — one who found out that translation was harder than they might have initially thought.

My thanks to those who helped me check bindings, track down acquisition records, and think through rebinding in general. This includes David Helliwell (former Curator of Chinese Collections, Bodleian Library), Julianne Simpson (Rare Books and Maps Manager, John Rylands Library), John Hodgson (Associate Director: Curatorial Practices, John Rylands Library), Yan He (Head of Chinese Section, Cambridge University Library), Sara Chiesura (Lead Curator for East Asian Collections, British Library), and Eva-Maria Jansson (Special Collections, Royal Danish Library). I am very grateful to Mark Elliott for helping me to identify the poem discussed here and generously sharing his own draft translation with me. Further thanks go to Elvin Meng for his insightful comments on an earlier draft of this post, and for helping me through some lines of the poem that had me stumped.

[1] See David McKitterick, Old Books, New Technologies: The Representation, Conservation and Transformation of Books since 1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); The Invention of Rare Books: Private Interest and Public Memory 1600–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[2] Lord Lindsay’s Library Report (1861–65), cited in John R. Hodgson, “‘Spoils of Many a Distant Land’: The Earls of Crawford and the Collecting of Oriental Manuscripts in the Nineteenth Century,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 48, no. 6 (2020): 1014.

[3] A black line indicates that the order of these two words should be reversed. I have reflected this reversal in both transcription and translation.

[4] A transliteration of qing chui 磬錘.

[5] I believe this is meant to be argiyame, “to prune.”